“Congratulations,” said the voice at the other end of the call. It was the fifth call Nere Teriba received in less than 10 minutes. There are also messages on her phone, which she plans to read much later. They are all congratulatory messages. “Go, girl. You rock!” reads the message staring at her as she peeped at her phone for the last time, repeating the words she had read almost inaudibly. Surprised at the sudden frenzy about a gold refining license her company secured months earlier, Nere smiles as she recalls months of hard work. Kian Smith can finally start smithing.

Starting in 2019, Nere Teriba, Vice Chairman of Kian Smith Trade & Co Ltd., will become the first and youngest Nigerian to refine gold locally.

“On one hand, we can say it took a few months, on the other hand, it took seven years,” says 36-year-old Nere Teriba as she tells The Nerve Africa how long it took the company to secure the gold refining license.

It was a meeting of preparation and opportunity for Nere, who had a proposal on a gold reserve buying programme for the country ready when she was invited to join the Economic Recovery and Growth Plan (ERGP) focus labs. Her proposal highlighted the need for a gold policy and a framework for gold refinery license permit structure for anyone who wants to apply for one.

The proposal by Nere’s Kian Smith made a case for the establishment of a Nigerian Gold Council which will be in charge of the country’s gold policy.

“The establishment of the council will drive innovation, stimulate the economy, and generate income for government coffers,” the proposal states. “Nigeria can become a gold economy irrespective of whether it mines gold or not. India, UAE, Singapore, Italy, Switzerland, Turkey and London are renowned world gold markets without the classification of gold mining countries.”

Kian Smith raised some important questions in its proposal, some of which formed the basis of our (TheNerve Africa) discussion with Nere when we met her at an art-themed tea room in Victoria Island, Lagos in October, weeks before the groundbreaking of her refinery.

Nere paused at different intervals during our conversation, politely explaining, each time, why she had to answer her phone calls. Nere runs a multimillion-dollar minerals, commodities and mineral services company, which has grown tremendously over seven years. Sleeves always up, ready to work, Nere plays in a male-dominated industry, where women sometimes have to work twice as hard to make the desired impact. To Nere, mining is a calling and she would give all it takes to help Nigeria and by extension, West Africa harnesses the mining economy.

How can the existing gold value chain be organized and strengthened? One of the questions posed in Kian Smith’s proposal stems from Nere’s belief that the Nigerian mining industry is not as broken as most people believe.

“The issue is not that there is no regulation, it’s just that they are not enforced,” explains Nere, who has plans on how to help the government solve some of the major challenges faced in the mining industry, especially as it concerns artisanal and small-scale miners.

Mining in Nigeria

Organized mining in Nigeria started in 1903 when the British Secretary of State for the Colonies established the Mineral Survey of the Southern Protectorate of Nigeria. In 1904, a survey of the Northern Protectorate was also established as the exploration of mineral resources for use as raw materials in Britain began. As a result, several mineral deposits including Columbite, Bitumen, Coal, Iron Ore and Gold were discovered. However, it was not until 1913 that Gold production started, peaking in the 1930s before World War II brought about a decline.

Nigeria had no choice but to participate in the war, being a colony of Britain. With Britain’s economic, industrial and military power weakened by World War I, the kingdom fell back on its colonies, using both their human and natural resources to prosecute WWII. Colonial companies abandoned mines during the war and the gold mining industry has not recovered since then.

Although in the 1980s the Nigerian Mining Corporation (NMC) resumed gold exploration, it could not sustain it. Fast forward to the 2000s, artisanal mining has become a thing in Nigeria, from Bin Yauri in northern Nigeria’s Kebbi State, to Bagega in Zamfara State where 163 people died from lead poisoning in 2010.

Artisanal Mining

Artisanal mining had peaked in Bagega when gold prices skyrocketed during the Great Recession. Even farmers left their crops and focused on mining. During the period, the price of gold went as high as $1,000 per troy ounce, so much that even small finds by small-scale miners paid well.

Till date, most of the mining done in Nigeria is done by artisanal and small-scale miners (ASM), making regulations difficult to enforce.

“The thing is, there has been a huge gap. We abandoned the sector, went for oil and the people took up the vacuum,” Nere explains, adding that their activities, while artisanal is not necessarily illegal.

“So, illegal miners are not necessarily artisanal miners. Sometimes, there are huge companies mining illegally. Mining illegally is if you are mining off permit and not following due process,” the Kian Smith boss explains.

With a renewed commitment to developing the mining industry, the Nigerian government, like others across Africa, is beginning to recognize how important artisanal and small-scale miners are to the growth of the industry. Hence, the government ministry in charge of mining in Nigeria is trying to formalise artisanal mining to ensure some form of regulation in the space.

Kian Smith is working with small and medium scale miners to source gold for its refinery. The company is also working with artisanal miners, whose activities it is going to be an important part of formalising.

“One of the major reasons several small-scale miners are not formalised is because of royalty payments, but we have found a way around this,” Nere says, explaining how Kian Smith will ensure the ASMs it works with are formalised. “One of the incentives we want to give our suppliers is paying royalties on their behalf.”

The idea seems to be working fine, as Kian Smith has been able to sign up 200 suppliers in less than three weeks. “We will help them get registered with the Corporate Affairs Commission in January,” Nere says.

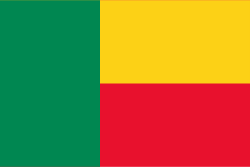

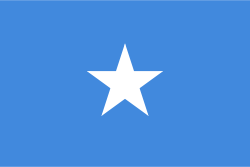

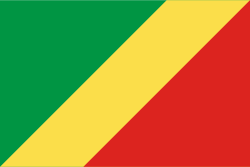

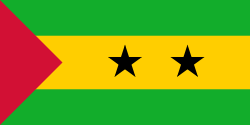

Kian Smith will also be sourcing gold for its refinery from other parts of Africa, including Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Tanzania. One supplier working across Ghana and Sierra Leone have already committed to supplying Kian Smith 100Kg of gold per month. In all, the company has signed Memoranda of Understanding with about 200 suppliers.

Although Nigeria is believed to have gold reserves of up to 200 million oz, there are no records to show exactly how much gold is mined in the country.

“But from my research, there are about 2 tonnes of gold physically in circulation each month,” says Nere. However, she admits that “we can’t quantify how much of that 2 tonnes is from neighbouring African countries, and how much of that 2 tonnes is mined locally”.

Nigeria’s neighbours have been more productive, with Ghana producing 95 tonnes of gold in 2015. Mali produced 50 tonnes in the same year and Burkina Faso produced 34 tonnes, but Nigeria could only manage 4 tonnes, as records show. Nere believes this figure shows how much the country could be losing by not formalising artisanal mining which even accounted for a huge percentage of the 4 tonnes reported in 2015. Most of the countries with decent gold production records in Africa have begun to recognise artisanal mining and are looking for ways to formalise their activities.

In Ghana, artisanal and small-scale miners, popularly known as galamsey have become increasingly important. They are responsible for all diamond production in the West African country and their contribution to gold production is increasing. The government is now training small-scale miners in sustainable mining methods as part of a roadmap that seeks to address illegal mining in the country.

Nere thinks there is a tech solution Nigeria can adopt. The Computer Engineering graduate said her company created a mobile solution — Zokia system, a mobile platform to register and bank artisanal miners.

“When we were doing our pilot in Chikun, Kaduna state, we registered 1200 artisanal miners, tagging the gold from mine, through the value chain, all the way,” she says. “We also used mobile money, as a way to eventually sensitize them, to get them off cash payment and keep their monies safe. More than 300 of the registered 1,200 use mobile money for payments.”

Nere explains that as good as the solution could be for formalising mining of all scales and reducing the incidence of illegal mining, artisanal and small-scale miners have no reason to spend money on tech, as they do not see it as essential to their business.

However, governments committed to reducing illegal mining to the barest minimum can pay for a tech solution such as Kian Smith’s Zokia System and make it accessible to artisanal miners for free. That could be a huge step in formalising artisanal mining, especially in Nigeria.

Read More: thenerveafrica.com